Do you know who really wrote the fiction book you’re currently reading? Did you buy it because you like the author, or were familiar with the book series, or are a fan of a particular literary genre? Well, the publishing industry is studying you. And getting ready for much higher profits. And, perhaps, starting to unconsciously engineer the beginnings of its demise.

As part of the irresistible spread of “sequelization” — by far the currently preferred business model in the entertainment industry (in 2024 every single one of the 10 most successful films has been a sequel) — the long-standing adoption by fiction publishers of “brand” and “franchise” strategies is accelerating. These strategies create an ideal host environment for AI to simply replace human authors in the near future.

The series as franchise; the author as brand

Successful authors have long had strong name recognition, and this, when combined with a focus on a particular literary genre, has in turn enabled the creation of highly successful multi-title fiction franchises. Examples are legion, ranging from Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot mysteries starting in 1916 and Ian Fleming’s James Bond series of novels in the 1950’s and 1960’s, to modern-day franchises like J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books, Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code series, Lee Child’s Jack Reacher novels, and so on.

Many of the more recent franchises have been collectively labelled as “airport novels” due to their ubiquity in air terminal book and magazine stands (owing to their popularity as rather light beach or poolside holiday reading), and their often shared characteristics of considerable length, fast-paced action, and somewhat cursory character development.

It’s a winning commercial formula. And one that is evolving. Some of the top-selling “airport novel” authors have now become brands in their own right, able to lend their name recognition to subcontracted writers for their established franchise, thus leveraging their loyal readership without actually being the author of the works.

James Patterson, one of the most prolific multi-genre authors in the world, collaborates with co-authors on nearly all of his books. His name is prominently featured on the covers, even though his co-authors often do most if not all of the writing. The long-lived Nancy Drew Young Adult/Mystery series, created by Edward Stratemeyer under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene, has continued to be written by ghostwriters maintaining that pseudonym as a brand for decades. And in 2020 the aforementioned Lee Child, author of the popular Jack Reacher action series, announced that he was passing series authorship to his brother Andrew, although the novels are still published primarily using the Lee Child name.

Most significantly, the author-as-brand has a proven ability to outlive the actual author. This trend started in earnest when the publisher of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels started to enlist other writers to continue the series after Fleming’s death in 1964. More recent examples of novels that continue to be posthumously published under the author’s name, or using it as part of the book’s cover and branding, include the Dirk Pitt adventure and NOMA action series by Clive Cussler (died 2020); the Jack Ryan espionage thrillers by Tom Clancy (died 2013), the Bourne and Cover-One action series by Robert Ludlum (died 2001), the Dune sci-fi series by Frank Herbert (died 1986) and the Flowers In The Attic Romance/Gothic novels by V.C. Andrews (died 1986).

When the game becomes bigger than mere books

The fact that most of these book franchises have been successfully and very profitably line-extended to films, video games, and television series makes the mainstream publisher’s franchise strategy all the more attractive. The longer a successful literary franchise can be sustained and amplified across multiple media and products, the greater the return. Once a franchise has been firmly established, authors become the least important ingredient in the formula.

Perhaps you can see where this is going.

If books can still prove popular thanks to their franchise attraction and established author-as-brand, irrespective of who actually writes them, readers will not really care (will they even know?) if the latest book in that franchise has been written by a machine instead of a human.

Enter AI. Exit authors?

Thanks to exponentially improving large language models used by the likes of Sudowrite, which can be used “train” AI to analyze and replicate writing styles and plot structures, publishers can crank out a “new” franchise and author-branded title in minutes and at negligible cost, without the delay and expense of having it written by a ghostwriter (let alone the original author). AI will increasingly be able to design and automate the marketing of the new title as well, zeroing in on its likely audience through a combination of targeted database and social media marketing.

It just gets better (or worse, depending on your point of view): AI also enables the creation of finely tuned variants of the work, each of which can be aimed at subsets of the targeted audience. A spy novel could have more technical and action-oriented language for those consumers (chances are, mostly men) whose readership profiles show a preference for that coloration, versus a more romance-oriented plotline for readers (mostly women in all probability) whose profiles show an affinity for that.

We could even get to the point of infinite customization based on individual reader personality and preference profiles: every digital copy of a title slightly different, and therefore unique. A free initial novel or two, especially if in e-book format, could even be offered to readers willing to complete an AI-powered reading preferences questionnaire, allowing the publisher to finely calibrate and sell future novels to the reader — perhaps via a subscription model — according to the provided input.

Goodbye tweed jackets, hello algorithms

This is all at odds, of course, with our mental image of book publishing as a rather staid and traditionalist branch of the entertainment industry. But hiding in plain sight is the relentless march of the digital platforms in their quest to be all things to all people, including people who read.

In addition to Kindle Direct Publishing (the leading publisher of self-published e-books), and Audible (the leading publisher of audio books), Amazon already owns and operates multiple book publishing imprints that cater to a variety of genres: Thomas & Mercer (Mystery and Thriller), Montlake Romance (Romance), 47North (Science Fiction and Fantasy), Amazon Crossing (Translations of international works), AmazonEncore (Rediscovered works), Two Lions (Children’s books), Little A (Literary fiction and memoir) and Skyscape (Young Adult fiction). Other digital platforms active in book and/or e-book publishing include Rakuten, Apple, and, in China, Tencent and Alibaba.

To imagine that these expansionist, cash-rich and highly astute platforms will stop snatching up traditional book publishers and publishing imprints is to not see the writing on the wall. And to believe that the owners and managers of these platforms will shy away from maximizing the profitability of the book publishing business through the use of AI-generated franchise and author-branded works is to fail to comprehend how AI will transform the economics and processes of pretty much any content-related industry.

Readers of the world, unite!

So far, so logical. But, as so often, there’s perhaps a catch. Once readers know for certain that the novels in their favorite franchises or by their favorite “author brands” have been written by machines, will they continue to enjoy those works as much as before? Will there not be a sudden crack in the heretofore emotional connection between humans writing and humans reading?

I think there will, but only if legislators step in and — like the artificial ingredients that must be listed on the side of food packaging — insist that the reader has a right to know who (or what) actually wrote the work in question. This will be necessary because, chillingly, the literary quality of the machine-produced titles will soon be indistinguishable from that of human-written ones.

Publishers will of course try to get around this by claiming that AI is being only used as a writing tool, and that actual authors are both the originators and operators of the AI technologies employed, providing plenty of “human” input alongside them.

But whatever the legislation, and whatever the publisher work-arounds, I fear the magic will have been killed. Much as it will be, eventually and sadly, when most painting, photography, poetry, animation, music and, in time, live action film and television is produced largely, if not entirely, by computers.

From ultra-processed books to organic?

We can look to another very traditional industry, food, for parallels of what happens when technology puts a foot where it is not really welcome. A very few years ago, lab-grown “meat” was the darling of future-oriented entrepreneurs and investors, who envisioned a wholesale shift to their product from the messy, cruel and environmentally ungreen business of raising, transporting, slaughtering and packaging livestock for food. But no matter how well the lab technicians replicated the taste and texture of animal-sourced meat, and how assiduously it was marketed, consumers just were not interested, citing “unnaturalness” as one of their main objections to the new products.

I could be wrong, but the very idea of artificially produced literary works could be just enough of a turn-off for most (or at least many) readers that they will flock instead to literary sources and platforms that purposely exclude AI-generated content, as Medium does (or at least tries its best to do). And this migration away from AI-powered book franchises and author brands that will have become formulaic and predictable, and instead towards more “open” platforms and distribution channels, may have the benefit of exposing more readers to new or “unbranded” writers locked out of the Big Publisher “machine.”

This may matter little to a mainstream publishing industry that gets progressively absorbed into the digital mega-platforms. These entertainment, e-commerce and social media Death Stars will be able to continue declining AI-powered book publishing operations at minimal cost until it’s no longer worth it. At which point they’ll shutter those operating companies as dispassionately as they have so many other companies they’ve swallowed.

Novels might end up like poetry: not yet gone, but going… going…

In the meantime and in parallel, it’s possible or even probable that we’ll see a gradual but inexorable decline of book-length fiction, whether in paper or electronic form. People are increasingly pressed for time, attention spans are getting shorter, and the infinite abundance of short-form entertainment, including literary, is an overwhelming distraction.

Think that’s improbable? Consider that even though the total volume of books sold increases moderately year on year, they are being purchased by a narrowing audience: nearly one in five U.S. adults who were reading novels or short stories in 2012 no longer did so in 2022, declining from 45.2% to 37.6% — the lowest share on record.

Add to this the probable disenchantment with machine-generated “literature,” and you can see how the mainstream publishers may be sleepwalking into a sinkhole partially of their own making.

Niche publishers catering to a highly selective audience seeking novelty, original voices and new writing talent may survive and even prosper, but the overall business of publishing novels seems destined to fade as a mass market industry. Finding success and riches penning novels might still be possible for a lucky handful of writers, but the risk-reward ratio of doing so will make it increasingly unlikely that many aspiring Harlan Cobens will continue to try.

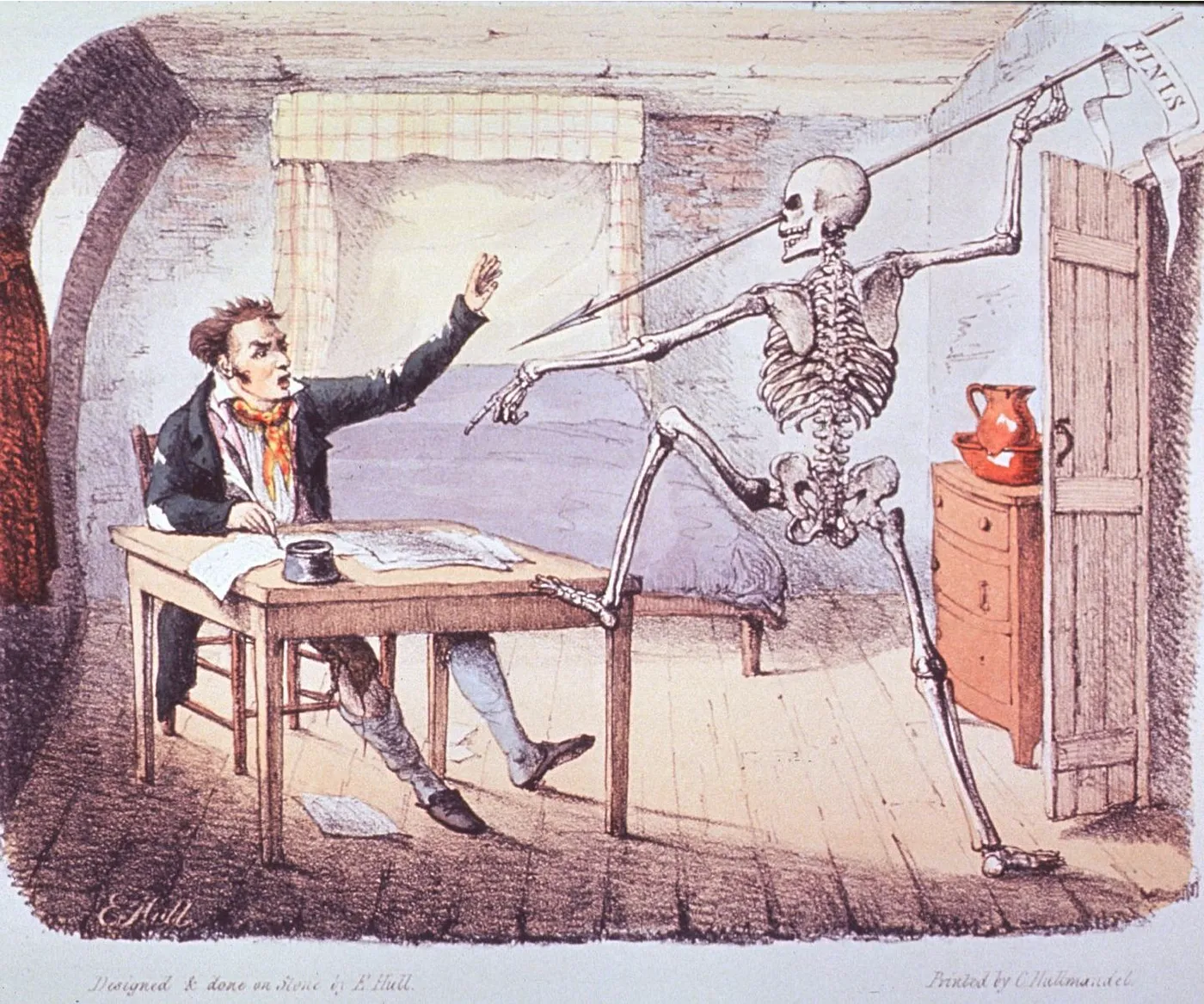

In short, and depressingly, “novelist” as a viable profession and an art, may, in our lifetimes, go the way of the telegraphist and linotype operator. If it does so, Artificial Intelligence will have played a significant role.

As with so many things in this speeding car we’re in, with no brakes or steering wheel, I can only hope I’m wrong.